UPDATE: GHADAMES

U. S. DEPT. COOPERATION AGREEMENT NUMBER: S-IZ-100-17-CA021

BY Jamie O’Connell, Will Raynolds, and Susan Penacho

The Collapse of Buildings at Ghadames

* This report is based on research conducted by the “Safeguarding the Heritage of the Near East Initiative,” funded by the US Department of State. Monthly reports reflect reporting from a variety of sources and may contain unverified material. As such, they should be treated as preliminary and subject to change.

The Old Town of Ghadames (غدامس) is one of five Libyan sites inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage List (1986). Consisting of a tightly clustered series of mud-brick houses in a palm oasis that served as a key nexus in the trans-Saharan trade routes, Ghadames is an outstanding example of a Saharan oasis town.

Ghadames is first recorded in history in connection with a Roman expedition to conquer the region in the late 1st century BCE [1]. Pottery sherds and Latin inscriptions discovered in and around the town indicate a Roman garrison was stationed there until the 3rd century CE. In 667, Ghadames, by then a Christian town, was conquered by the Arabs under Uqba ibn al-Nafi.

A view over the interconnected rooftops of the Old Town of Ghadames (Al Jazeera; May 1, 2014)

The labyrinthine urban plan of Ghadames has long attracted and welcomed visitors (National Geographic, March 27, 2013)

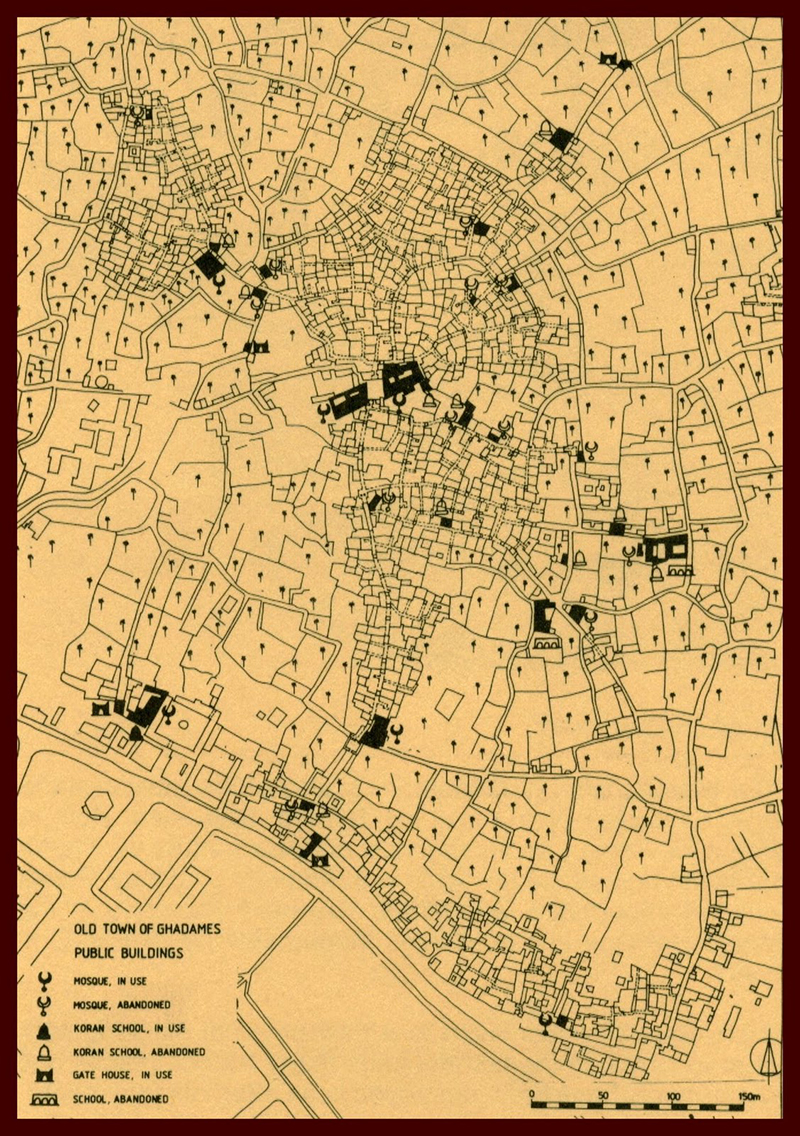

Map of the Old Town of Ghadames (Mirath Libya; July 2, 2012)

View of Younis Mosque in the Old Town of Ghadames (Franzfoto/Wikimedia; November 27, 2010)

Locals work with experts to repair al-Atiq mosque in the Old Town of Ghadames using traditional techniques and materials (Archnet/Abdulgader Abufayed; 2002)

The project, which cost around $5 million USD, involved rebuilding private houses, renovating water works, revitalizing agriculture using locally available materials, and improving tourist services, all using local labor. The project aimed to preserve cultural heritage and local knowledge, while also promoting tourism and economic diversification.

In 2008, as part of another nation-wide tourist development scheme managed by the Libyan consulting firm Engineering Consulting Office for Utilities (ECOU), preparations were made for large-scale conservation work to be carried out in conjunction with CRATerre-ENSAG, the premier French school specializing in the global practice of earthen construction and restoration. CRATerre conducted a number of tests to formulate an appropriate mixture for adobe bricks and mortar on the basis of local materials.

CRATerre staff produced adobe bricks at Ghadames (CRATerre; November 24, 2008)

A building in Ghadames collapsed due to intense rain and lack of maintenance (Mahmoud Hadia, December 27, 2017)

Some sections of a building in Ghadames cracked extensively and are close to collapse (Mahmoud Hadia, December 27, 2017)

Following a complaint from the Department of Antiquities (DoA) in Ghadames regarding collapses, the DoA in Tripoli dispatched a delegation to the site to document the aftermath of the storms. This effort is part of a larger DoA project to prepare comprehensive reports on the status of each of the five UNESCO World Heritage sites in Libya, all of which are currently listed on the World Heritage List in Danger. Mahmoud Hadia and Safa al-Hagi of the archives team in Tripoli documented damage for their internal report, and provided ASOR CHI with photographs of the damage to the Old Town of Ghadames, including collapsed mud-brick structures weakened by rains and lack of maintenance.

Since the visit of the delegation from Tripoli at the end of 2017, several additional buildings have collapsed. According to the DoA, moisture that penetrated the walls during the heavy rains caused the mudbrick walls to swell. As they dried out, these walls began to gradually buckle, resulting in significant structural damage.

DoA employees in Ghadames have continued to document these ongoing collapses, and report that they expect more damage in the future as temperatures continue to rise in Ghadames during the transition from spring to summer. Hassan Hammoudeh has been directly in contact with ASOR CHI, and has provided descriptions of the most recent damage. Hammoudeh identified five previously unrecorded instances of collapse. He reports that neither the DoA nor the Historic Cities Authority, which is nominally in charge of the site, have been able to provide assistance due to the lack of an an operating budget. The newly reported collapses occurred at five locations, namely four residential buildings (Location 1, 3–5) and one disused Sufi school (Location 2).

Relative locations of recent instances of collapse (DigitalGlobe NextView License; December 16, 2017)

A view of Location 1, where portions of two adjacent houses separated by a partition wall have collapsed. Date palm trunks and woven mats that once supported the floors and roof can be seen in the debris pile (Hassan Hamoudeh; April 4, 2018)

A view of the scar of the collapsed partition wall that once separated two houses (Hassan Hamoudeh; April 4, 2018)

The interior of one of the two houses at Location 1. Cracks have proliferated in the lime plaster of this wall, suggesting that the earthen mass behind it has started to shift and may soon collapse (Hassan Hamoudeh; April 4, 2018)

An exterior view of the collapsed school (Hassan Hamoudeh; April 4, 2018)

A view of a debris pile where the roof and interior walls of the Sufi school collapsed (Hassan Hamoudeh; April 4, 2018)

A DoA Ghadames employee examines the damage to the collapsed roof of the school. Many of the timbers remain intact (Hassan Hamoudeh; April 4, 2018)

Sections of collapse, like those at Location 3, may be stabilized using infill of adobe brick. If such actions are taken swiftly, it is possible to save the structure as a whole (Hassan Hamoudeh; April 4, 2018)

A close-up view of the collapse of a section of a wall at Location 3 (Hassan Hamoudeh; April 4, 2018)

Damage to an exterior wall and entranceway at Location 4 (Hassan Hamoudeh; April 4, 2018)

A view of the palm wood supports in the passageway near Location 4, which are beginning to buckle and crack (Hassan Hamoudeh; April 4, 2018)

The entrance passage of this house showed signs of collapse and has been stabilized with provisional shoring (Hassan Hamoudeh; April 4, 2018)

A view of a collapsed house near al-Atiq Mosque (Hassan Hamoudeh; April 4, 2018)

An exterior view of collapsed house near al-Atiq Mosque (Hassan Hamoudeh; April 4, 2018)

A debris pile from a collapsed house near al-Atiq Mosque (Hassan Hamoudeh; April 4, 2018)

Some of the walls at Location 5 remain standing but have separated entirely from other nearby walls, suggesting that collapse is imminent (Hassan Hamoudeh; April 4, 2018)

A view of one of the smaller outbuildings associated with the house at Location 5 (Hassan Hamoudeh; April 4, 2018)